Chapter One

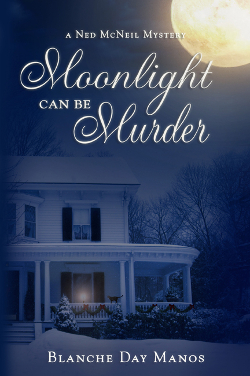

My car’s headlights cut a yellow swath through the swirling snow. Forty years ago, Uncle Javin’s driveway had not seemed so long but memories dim with time. Gray clouds with their burden of snow, trees crowding either side of the driveway, plus the lateness of the December day made it impossible to see more than a few yards ahead, but at last the dark shape of Javin Granger’s Victorian house loomed through the winter twilight. The sight brought a lump to my throat as I thought of the last time I had seen this lovely home.

My parents and I had lived on the other side of my hometown of Ednalee, Oklahoma. We visited Uncle Javin often and I, as a youngster, had run all through the upstairs, downstairs, and the basement, but those visits ended when he was sent to prison, in 1974 for killing his neighbor, Eldon Decker. The house which Mom called the old home place was locked and remained empty until he was released from prison only last year. When I was twelve, my parents and I moved to Atlanta and there had been no need to return to Ednalee—until now.

It seemed strange that no light shone from the living room windows. Surely Uncle Javin had re-established his account with the electric company. I had written to tell him when I would be arriving but his residence was certainly not glowing with welcome. Even though he didn’t have a phone, I remembered that my grandparents had wired the house with electricity many years ago.

My uncle had sent me two letters, the first one mailed three weeks earlier and written in the shaky hand of the aged.

“Please come, Nettie,” he had written. “You need to come home.”

His letter was noteworthy not only for its terseness but also for its rarity. Never had my mother’s older brother written to me. And then, a few days later came the second message: “You’ve got to get here soon. I must talk to you. Strange things are happening, and there’s something you should know before it’s too late. Please stay here in my house. I think you’ll be safe enough. Hurry.”

Those words shocked me. There was something I should know? And why should there be any question about my safety? I started making plans to close my Atlanta apartment, pack my suitcase, and drive the 800 miles to Oklahoma.

My mother had died only last year and Dad, the year before. Mom’s younger brother, too, suffered a fatal fall while repairing the roof of his house. I was an only child and grew up without cousins. My husband Sloan and I had not been blessed with children, and I had been a widow for five years. My uncle’s letters made me realize that I did not particularly relish the idea of being left on this earth with no family, and Uncle Javin’s letters worried me. Was he in danger? His concern came through in his letters. He needed me and this seemed even more important than my job as a bookkeeper with Krohman Department Store.

Besides, there was another, more sinister reason for leaving Atlanta. It had to do with something I saw, or perhaps something that someone thought I saw.

One evening in October, I went shopping at a near-by mall. When I left the store and started walking back to my car in the crowded parking garage, I noticed a flurry of activity in the aisle behind me. Two men, dressed in sweaters and knit caps held the arms of a third, well-dressed man, and were hustling him toward a long, dark car.

Evidently, the third gentleman did not want to go with these two and was putting up a fight. While I stared, shopping bag slipping from my hand, the man wearing the suit shouted, “Help me!” and he was looking straight at me.

I yelled for them to stop but the two assailants pushed their victim into the dark car, jumped in, and sped off. As they drove under a light in the garage, I glimpsed the car tag. I called the police, reported a possible kidnapping, and gave them the car’s description and tag number.

The next day, the Atlanta papers were rife with the story. Congressman Edward Langlier had been kidnapped. The car had been located, but the Congressman had not.

Since I was the only witness, I had spent some time in the police station, describing what I had seen. No, I had not gotten a good look at the kidnappers but I thought I might be able to recognize them again. Possibly.

After that, strange things started happening. I would notice a car following closely behind mine. I got five or six phone calls; just calls with no number or name on caller ID and nobody on the other end of the line. A dead bird showed up at my apartment door, and I got an anonymous letter with words clipped from a newspaper advising me to forget what I saw.

Now, I’m no coward but then, I’ve never considered myself overly brave. I reported these instances to the authorities, took them the letter and dead bird, but they seemed unable to get any leads. They simply told me to be careful and keep in touch.

In that large, impersonal police force, one particular detective took a special interest in the case. Detective Max Shelman phoned several times to ask if I was all right. He had even taken me to lunch once, after I had gone to the station with anonymous note in hand. Max Shelman was of medium height, slim, with brown hair cut very short, brown eyes, and an engaging warmth about him. I felt that, with a little encouragement, he could become a friend, but I simply was not interested. With Sloan’s death, the romantic part of my life died with him. I simply didn’t have the energy nor inclination for another attachment that could be severed suddenly and without warning, leaving me with an even more damaged heart.

So I did a most extraordinary thing. I, Nettie Elizabeth Duncan McNeil, resigned from my job, packed my bags, climbed into my black Ford Escape, and headed west.

Dad and Mom had never wavered in maintaining Javin’s innocence even though the man himself confessed, more than forty years ago, to the murder of Eldon Decker.

“He didn’t do it,” Mama had said. “He’s protecting somebody.”

Dad would nod his head and mutter, “Sure as the world, that’s what he’s doing.”

However, the jury in Edna found Javin guilty and sentenced him to forty years in the state penitentiary. My parents were crushed. A small town has its share of gossips and armchair jurors and my hometown of Ednalee had become uncomfortable for us. We moved to Georgia and began a new life there.

The white two-storied house gradually emerged from the curtain of snow, its wood-framed appearance majestic in the twilight. I parked in front of the wrought-iron fence surrounding the Granger yard. Scooting out of my SUV, I yanked one suitcase from the rear seat and locked the doors behind me. Tomorrow would be time enough to unload more luggage. Right now I felt an urgency to talk to my uncle.

Pulling my flashlight from my purse, I pushed open the gate and waded through the snow toward the house.

The two-storied residence was built in an L-shape, with a square porch in the angle of the L. Steep wooden steps led to this porch. It was a relief to step under its sheltering roof. I raised the brass door knocker, banged it loudly against the large strike plate, and waited. Not getting any response, I knocked on the door.

“Uncle Javin!” I called. “Uncle Javin, it’s Nettie.”

Still, no answer. I was beginning to shiver from the cold and also from the strangeness of standing outside the silent, familiar old house. Set back from the street and surrounded by trees, this imposing Victorian was isolated from any near neighbors. No one in town knew I was here. Nobody would be checking to see if I had arrived safely.

I took hold of the doorknob and pushed. Creaking mightily, the heavy door swung on its hinges. Inside was as dark as pitch. Shadowy shapes of loveseat, chairs, and tables appeared in the beam of my flashlight.

Something was wrong here. My uncle had asked me to come. He knew when I would arrive, but where was he?

Finding the light switch by the door, I pressed it and the crystal chandelier hanging from the ten-foot ceiling blazed, revealing a deserted parlor, silent and cold.

My flashlight no longer needed, I walked hesitantly through the parlor and into the dining room. A few coals glowed in the fireplace in the dining room, like red eyes winking at me. Uncle Javin and my grandparents before him, had used this large room as a combination living/dining area mostly because the fireplace made it warmer. In the summer, the family ate in the small sunroom just off the dining room or in the kitchen itself. I didn’t bother turning on other lights until I got to the kitchen.

“Uncle Javin!” I called, at first softly, then louder. “I’m here! Where are you?”

I flipped the light inside the kitchen door and the sudden brightness revealed that it looked exactly as I remembered it. Evidently, my uncle did not believe in updates or simply liked the kitchen the way it was. It was a small room with outdated fixtures, the kind featured nowadays in antique shops; however, those fixtures shone. A wood table with four chairs, gleaming white stove with yellow trim, small refrigerator and single porcelain sink, a yellow vinyl cabinet top free of clutter; but, there was no aroma of food or fresh-perked coffee. The room had an empty, unused feel.

Where was Uncle Javin? What should I do now? I gripped my cell phone in my coat pocket. Who should I call? What acquaintances were left in my home town?

Something brushed against my leg. I jumped and yelped. A small, gray cat gazed up at me with solemn, unblinking eyes and then commenced twining around my ankles.

Relief flooded me. At least there was something alive and moving in this silent house. I knelt down and ran my hand over the cat’s sleek fur.

“Are you hungry?” I asked softly. “Is your food dish empty?”

The cat arched her back and turned around to trot toward the laundry room.

Perhaps Uncle Javin had to leave for some reason before he put out food for his pet. Or maybe he lay somewhere in the house, injured or ill. He was, after all, elderly and he lived alone. Feeding the cat seemed to be top priority, then I would search every room until I either found my uncle or knew for certain that he was not here.

I followed the cat into the small room next to the kitchen.

A washer and dryer lined one wall. An ironing board lay on its side. My heart seemed to stop. Two legs wearing tan corduroy pants stretched out under the ironing board.

My breath caught in my throat and I edged farther into the room. Half-hidden by the washer and ironing board, lay my uncle. One arm was stretched out beside him, first clenched; the other arm was under him. Blood seeped from an ugly, dark blotch on his brown checked shirt.

I fell to my knees and gently raised his head. He attempted to smile. Tears filled my eyes. Uncle Javin had been in his early forties when he was taken to prison, a vigorous man with dark, curly hair and twinkly blue eyes. Now his hair was gray and thin. His eyes were the only thing that looked familiar.

“Nettie,” he whispered. “You came home.”

Tears blurred my vision.

His breath caught and he coughed. I had to bend close to hear his next words: “Be careful, Nettie. Don’t trust…” He gulped, struggling to breathe.

I put my ear close to his lips.

“Don’t trust who, Uncle Javin?”

“Rose—Find it, Nettie. Important…” His lips moved but I could hear no further words.

“Rose? Do you want me to find a rose?”

Uncle Javin sighed and closed his eyes. I had come home but I was too late. My uncle was gone.

This must be a bad dream. Surely, I would wake up soon. I looked around the room, searching for anything that would make sense of the scene before me. Everything appeared to be neat with nothing out of place except the over-turned ironing board, and, of course, my uncle with the hole in his chest. Without being told, I knew that it was a bullet hole or a knife wound. An unknown person had snatched Uncle Javin’s life from him. His letter said strange things were happening. Had attempts been made on his life before today?

A black object protruded from under the washing machine. I gingerly poked it, and the handle of a gun slid into view. Guns were not my area of expertise and though I owned one, I didn’t like them. But as I picked it up, I knew that it was a revolver. It felt cold and looked deadly and it didn’t take much guess work to ascertain this was probably the thing that had been used to snuff out my uncle’s life. But whose was it? Who had pulled the trigger?

A scream shattered my thoughts. I pivoted and jumped to my feet just in time to see a bowl filled with food hit the floor and break. A short, plump gray-haired woman stared at me with large, frightened eyes. Putting up both hands as if they were a shield, she croaked,

“Please, please don’t shoot me too.”

That gun was still in my right hand, pointing in the general vicinity of the woman. Guiltily, I placed it on the floor.

“No, no,” I said, “I didn’t shoot him. I don’t know who did. He was here on the floor when I came in.”

The woman delved into her coat pocket and pulled out a cell phone. “Stay away from me,” she yelled. “I’m calling the police.”

She started backing up and when she reached the kitchen, she whirled and ran as quickly as a person of her ample girth could run, toward the front door.

I didn’t follow her. Sighing, I looked down at my uncle. I had just found him after forty years and now he was gone. Who had killed him and why? Calling the police sounded like a very good idea to me.

Chapter Two

The officer who had escorted me to the police station, a young, slim man named Gerald Mills, opened the door to the office of the chief of police. He indicated a straight-backed, wooden chair which faced a broad, cluttered desk. A bronze name plate stated that the desk was the property of Cade Morris. A memory stirred deep within my mind but I was too upset to pursue it.

“Have a seat, Ma’am,” said officer Mills. “The chief’ll be with you in a minute.”

I sat on the edge of that chair, twisting the straps of my purse, swallowing back my tears. The woman who found me beside Uncle Javin had, indeed, called 911. She told them I shot my uncle and very nearly shot her too. No matter how much I protested, the two policemen answering the call asked me to accompany them downtown. This was after they had notified EMSA and the EMTs took my uncle away.

The small room seemed cold to me. I shivered and pulled my long, wooly coat closer.

“Would you like some coffee, Mrs. McNeil?”

I looked up at the man who belonged to that deep, soft voice. This, I supposed, was the Chief of Police of Ednalee, Oklahoma. He was tall, broad-shouldered, and he looked good in faded Levis. Gray liberally sprinkled his short, dark hair and mustache. Blue eyes, the color of a cold December sky held mine.

Gratefully, I took the steaming brew he held out to me. “Thanks”, I mumbled, cradling the warm cup in my hands.

He sat down behind the desk. “Cade Morris, ma’am. You are, I believe, Nettie McNeil?”

I nodded and swallowed a mouthful of coffee.

“Officer Mills tells me that you are old Javin’s niece?” he asked.

I corrected the “old Javin” with, “I’m Mr.Granger’s niece, yes.”

“Well now, Mrs. McNeil, I’m sorry about your uncle. I knew him and regarded him highly.”

“You did?” I blinked. He regarded my uncle highly even though Javin had served time for killing someone?

Cade Morris nodded. “Now then, suppose you just tell me, in your own words, exactly what happened. Go as slowly as you need. I’m in no hurry.”

So, between gulps of hot coffee and frequently wiping tears from my eyes, I told him about Uncle Javin’s letters, my drive from Atlanta, and finding his body. I even told him about the cat.

As I talked, the chief scribbled in a small notebook. No stenographer nor tape player here, just a pen and paper for writing up reports.

“I found that gun under the washing machine,” I finished. “I shouldn’t have touched it because now my fingerprints are on it but I was too upset to think about that. I promise you I did not kill my uncle and I was not about to shoot that—that woman.”

He supplied the name for me. “Martha Decker.”

Drawing a shaky breath, I looked down at my Styrofoam cup, damaged beyond holding more coffee. I had absently-mindedly torn bits off the rim as I talked.

Cade Morris stared at me for so long, heat crept up my neck and onto my face. At last, he half-smiled and said slowly,

“I place you now. You’re Ned Duncan. I sat behind you in Miz Thornton’s room at Edna Elementary.”

Staring at the chief’s salt and pepper hair and mustache, a half-formed memory emerged. About two feet of height disappeared and I realized why he seemed familiar. We had indeed been in the same room but not the same grade in elementary school. My home room teacher put me in a writing class with a group of older students. Creative writing was my favorite subject and I excelled at it. The boy Cade Morris teased me about my red hair and freckles but he punched another classmate during a long ago recess who had done the same thing. He and the other school children shortened my long name, Nettie Elizabeth Duncan, to Ned. I hated the nickname.

His was the first familiar, live face since my arrival in Edna and I’ll confess the room seemed a little less chilly. It was good to see someone I knew, even if that someone had once been a pest and was probably wondering if I was guilty of killing my uncle.

Cade cleared his throat. “I don’t suppose you would happen to have your uncle’s letters with you?”

So, he didn’t entirely believe me and wanted proof.

“Thankfully, I do have,” I said, delving into my purse and bringing out the folded and re-folded pages of lined paper.

Anxiously, I fidgeted with the Styrofoam cup while he read the letters. His eyes narrowed as he looked up. “Do you mind if I keep these?

I refused to be intimidated either by his office as chief of police or his direct gaze.

“How about just making copies and giving me the originals?” I asked.

A grin tugged at the corner of his mouth. “How about my keeping the originals and giving you the copies?”

I shrugged and he called Officer Mills to run off the duplicates.

Cade seemed to be thinking out loud. “It seems that your uncle may have been afraid for his life. I wish he had notified us of his suspicions. You say he asked you to find something?”

“Yes. Actually, Cade, um—Mr. Morris—I can understand that he might not trust law enforcement. His association with the police was not pleasant, as you know.”

“How about his mental outlook? Do you know that? Did he contact you before or after those letters you brought with you?”

Shocked, I answered, “No! He never did. Why do you ask? Do you think he shot himself?”

Cade leaned back in his chair, half-closed his eyes, and regarded me thoughtfully. “It was bound to be depressing, coming back to the town where the murder happened, even if it was a long time ago. Maybe he felt alone, maybe he didn’t see much of a future.”

I swallowed. Why hadn’t I kept in touch with my uncle? Of course he felt alone. He was alone, and I, his next of kin, had not given him any support.

“Actually,” Cade mused, “I didn’t think he seemed despondent either. He seemed determined to make a life for himself here. It’s funny that Martha Decker was there just at the same time you were. She said she was bringing your uncle a casserole. Said she does that quite often.”

“What’s funny about it?” I asked. “I assume she is a neighbor, somebody trying to be kind to a lonely old man.”

Never mind that she had jumped to an entirely wrong conclusion. She must have a good heart.

Cade Morris pushed his chair away from his desk, crossed his legs, and frowned.

“It’s funny ‘cause Martha Decker might have been trying to be friendly to a lonely old man that a lot of people shunned, but she also happens to be the step-daughter of Eldon Decker, the man Javin Granger killed.”

I nodded. Strange, yes, but somehow irrelevant. At that moment, I just wanted to sleep for a month in a warm, comfortable bed. Perhaps, when I woke up, I’d find myself in Atlanta and my return to Edna would be only a bad dream.

Moonlight Can Be Murder will be available later this year from Pen-L Publishing.